The Cheviot Sheep

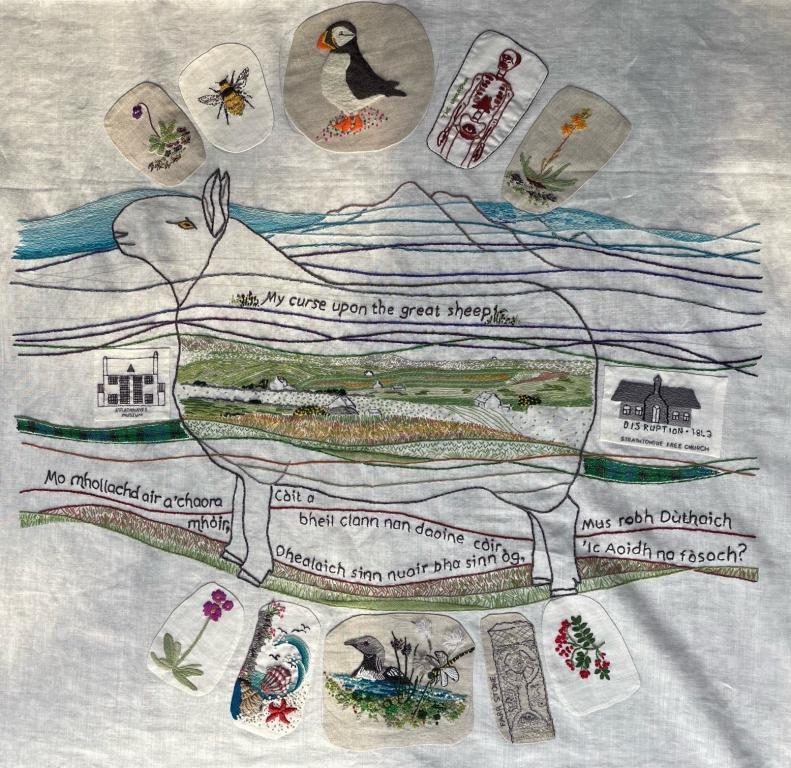

The Farr North Stitchers came together from Strathy to Tongue to stitch the story of the North Coast, its communities and a curious Cheviot Sheep and its central role in the natural and cultural heritage of the Highlands and Islands.

This is their story.

Sheep have been a part of the region's agricultural scene for centuries, providing sustenance and economic security for generations of Highlanders. In the past, sheep provided milk, wool, meat and even manure for crofters to use as fertiliser. The historic extent of this economy in the region means it is home to a number of hardy breeds including the feral Soay sheep of St Kilda, Hebridean sheep and the subject of this panel, the Cheviot Sheep.

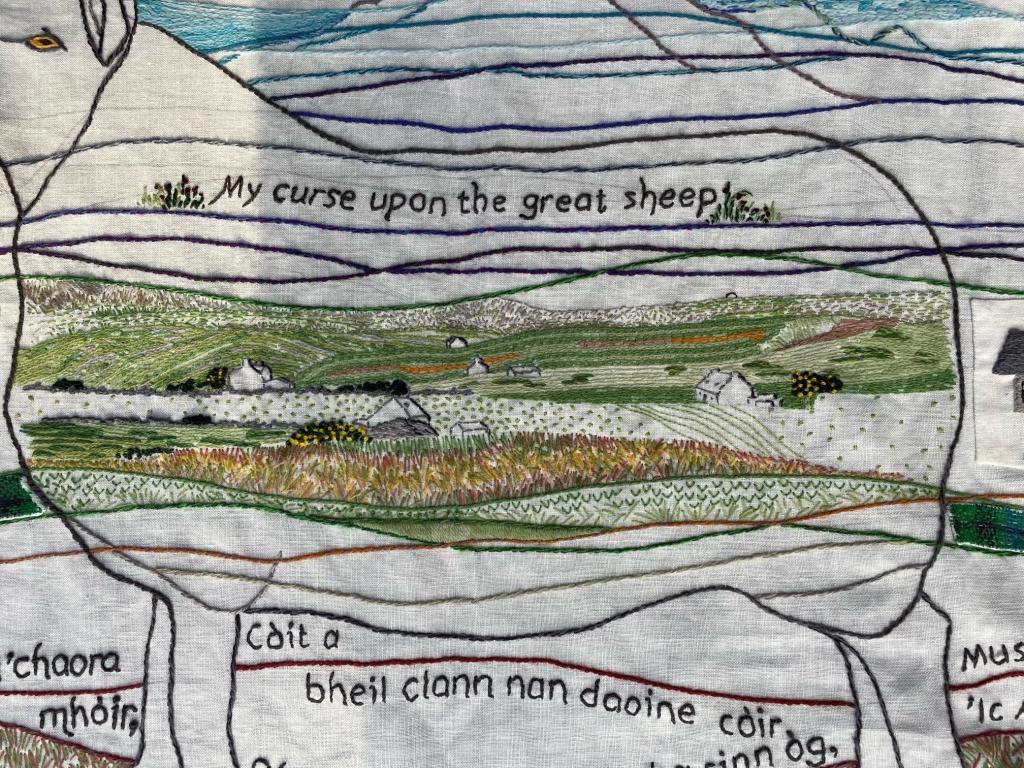

Taking their name from the Cheviot Hills, which straddle the Anglo-Scottish border, the Cheviot Sheep was first introduced to the North Highlands in 1791 when Sir John Sinclair brought 500 ewes to Caithness and Sutherland. Their arrival, however, was at the height of the first phase of the Highland Clearances - a period of forced migration and land evictions from the Highlands. The Clearances removed most of the crofters from their land, leaving it open for large-scale sheep farming, which allowed for the creation of vast sheep farms. This influx of sheep meant that landlords were able to reap large profits from the wool industry at the expense of, and with no regard for, the Highland people.

The year 1792 would mark Bliadhna nan Caorach ('the Year of the Sheep'), observed by historians as not only an extension of existing legal and class conflicts but also a protest over the effects of this influx of sheep to the local environment.

While sheep continue to play an important part in the region’s economy and culture, the Clearances ultimately changed the face of the Highlands forever and had irrevocable repercussions on Gaelic culture which are still felt to this day.

The Cheviot Sheep surrounded by interesting local stories.

The Cheviot Sheep surrounded by interesting local stories.Image provided by Sophie Gartshore

BEHIND THE PANEL WITH THE FARR NORTH STITCHERS

MORE TO THE NORTH COAST

When thinking about our panel, we all wanted to tell a story of communities and people - not just sheep. We wanted to show the landscape, its colours and textures. The wide horizons, and small communities of scattered cottages. Stitchers live along the North Sutherland coast from Strathy to Tongue - a beautiful area with small and vibrant communities, amazing coasts, mountain and moorland.

- The Farr North Stitchers

THE JOURNEY STONES

STRATHTONGUE FREE CHURCH (YVONNE BROWN)

The Disruption of the Church of Scotland, which led to the foundation of the Free Church in 1843, was the most important ecclesiastical event in modern Scottish history and has no parallel in the histories of the other nations of the British Isles. The evangelicals - those who opposed the patronage system which allowed local landowners to appoint ministers - were led by Thomas Chalmers (1780-1847) and abandoned the church in which generations of their families had worshipped and established a new church which soon rivaled the established church in many areas in terms of adherents, communicants and - eventually - church buildings and manses. The repercussions of this event went far beyond religion: the role of the Church of Scotland when it came to education, poor relief, charity, and rites of passage was now compromised. It became hard for it to claim superior status in many areas, particularly in the Highlands. Instead, Free Church members claimed for themselves the legacy of the Reformation and were notable for their commitment to the reform of politics, stern self-discipline, and their belief in self-improvement.

Free Church adherents could now elect their own ministers and had to build their own churches to worship in. (Problematic in itself as the Duke of Sutherland along with other landowners, refused sites for Free Church buildings). In 1843, the Minister of Tongue adhered to the Free Church (along with his son as his colleague) but both died within a month of each other in 1845. In terms of the congregation, all of the people in the eastern district of Tongue, estimated at around 1400, adhered to the Free Church (apart from 9 families). The congregation at first worshiped in a tent until a suitable site was obtained - Strathtongue Free Church (and Manse), along with many others, was built in the 1840s and opened its doors in 1847 with the Reverend Hugh Mackay Mackenzie as its minister. The church itself could seat 750 worshippers with plenty of standing room too! Acting as the Free Church for the whole of the Tongue area until 1900 when the congregation passed to the United Free Church and to the Church of Scotland, as Tongue Strathtongue in 1929. In 1937, Tongue Strathtongue was joined with the congregation of Tongue St Andrew’s, under the name of Tongue.

Overall, the significance of the disruption in the Highlands was enormous. In all but the Catholic areas, c90% of the population left the established church. In Sutherland, it was reportedly 99.8%. On the first Sabbath following the disruption, a dead dog was hungover the pulpit of the established church in Farr! The impact of the Disruption in the region was dramatically heightened by two factors - eviction and famine. (This resonated with anti landlordism and poverty in the lowland cities and forged embryonic political similarities with the rural and urban working classes.). The Disruption was an ecclesiastical matter which clearly filtered into much of the social, economic and political landscape of the entire country. The Free Church was decided anti-landlord and it helped mould a political consciousness which in the next quarter of the century would help towards the establishment of the Crofters’ Party- arguably th first party in the UK representing working class interests. With 5MPs elected in the 1885 election, following theReform Act of the previous year) and the successful passing of the Crofter’s Holdings (Scotland) Act (1886) which, amongst other things, granted security of land tenure to crofters and established the Crofters’ Commission, the working classes of the Highlands and Islands, finally had voice. Thus, the political consciousness which had been aroused and moulded by the disruption of 1843, was helping to impact upon the lives of those living in the Highland region and would continue to do so for the remainder of the century. As James Hunter notes, ‘In the Highlands, the Disruption was not just an ecclesiastical dispute. It was a class conflict.’

Sources: Religion and Society in Scotland since 1707, Callum G Brown (1997), The Making of the Crofting Community, James Hunter (1976), Statistical Accounts for Scotland, HCA/CH3/449/1, Tongue Free Church, United Free and Strathtongue Church of Scotland Session Minutes 1843-1933. Thanks to Highland Archives Centre and Professor Catriona M M Macdonald.

The Disruption journey stone.

The Disruption journey stone.Image provided by Yvonne Brown

UNKNOWN (Yvonne Brown)

My journey stone of the Unknown in no way does justice to the enormous public sculpture by Kenny Hunter at Borgie Breco due to the size constraints of the journey stone. The entire sculpture could not logistically be fitted into the small piece of linen therefore only the head and torso have been embroidered. I only hope, therefore, that it represents in a small way, the spirit of the Unknown.

I contacted the artist to ask if he would mind me including the Unknown in our Farr North Stitchers’ panel and he was happy for me to do so. I further contacted Kenny Hunter to ask if he could send me a description of the Unknown as I felt it was important to learn about the sculpture from him so what follows are his words….

The Background

Throughout the world there are many stories of Monsters and Giants, generally they are ‘outcasts’ condemned to exist in a remote or barren places. Scotland has an empathy with this tradition, indeed much of its history has been defined by characters and events marked by sacrifice and exile, such as William Wallace, Bonnie Prince Charlie and the Highland Clearances.

The Site

‘The Unknown’ overlooks the Strathnaver and Borgie Glens, the site of one of the most infamous and traumatic clearances in Scottish History. In this area you can also find, not only the ruins of cleared villages, like Rosal, but Earthworks, Duns, Forts and Chambered Cairns from earlier Neolithic, Iron and Bronze Age people.

Beyond this tangible human history there are numerous supernatural local stories that are also indivisible from this landscape, featuring Ghosts, Monsters, Seal people and Giants. There is a widely known legend of two giants of whom it has been said fought and threw boulders at one another at the mouth of the Naver river. This type of oral tradition is a continuing part of Highland Culture and ‘ The Unknown’ has been conceived in response to it as well as to the recorded history of the area. The aim of the artwork is to absorb and reflect this without directly addressing one aspect of it in particular.

The Sculpture

As ‘The Unknown’ is physically distant from the major population centres of Scotland, for some the journey to see it will form an important part of how it is understood. The context and the sculpture come together to define the outcome of this artwork.

The human skeleton can evoke many things, perhaps the most emotive being our ancestral past and our shared humanity.

A tribute to the Unknown.

A tribute to the Unknown.Image provided by Yvonne Brown

ROWAN BERRIES (Patsy Macaskill)

So many houses around this area have a rowan tree in the garden or nearby. It almost seems odd when its not there!

These trees have a long and sacred history.and have been planted beside homes for very many centuries. They protect the house and its occupants from witches, and should never be cut down. Important in Celtic mythology, and known as the Tree of Life, the trees symbolise wisdom, courage and protection. Carrying Rowan twigs on your person was a way of using the rowans protective qualities to keep you safe from threats of evil spells and witchcraft.

Journey stones reflect the special qualities of the area.

Journey stones reflect the special qualities of the area.Image provided by Sophie Gartshore

OUR EXPERIENCE

Great to meet up with fellow stitchers and do something creative together.

Super to share ideas and adapt our panel design to include thoughts from all of us and super group with a wonderful mix of interest and skills that came together to produce a 'work of art'!

New friends and inspiration to do some more creative things together.

- Farr North Stitchers

DISCOVER MORE STORIES FROM OUR GROUP

Feeling of the Flow Country

On the Edge

My curse upon the great sheep.

My curse upon the great sheep.Image provided by Sophie Gartshore

WITH THANKS TO THE FARR NORTH STITCHERS

This panel was stitched by Yvonne, Bryony, Jane, Patsy and Sarah who gave their time, skill and energy to completing a fantastic artwork for their area.

If you would like to see the panel up close and admire the detail of their work, you can currently view the panel in the Inverness Castle Experience.

EXPLORE MORE STITCHERS STORIES BELOW

Swipe left for more