A Stitch in Time: The Wedding Gown of Isabella MacTavish Fraser

Hello and welcome back to our Spotlight series ‘Behind the Story’. In this series we take a closer look at the fascinating history behind stories which have been shared with us on the Spirit: Stories archive.

This week, inspired by the story ‘Isabella MacTavish’, join us as we take a look at the hidden history behind the iconic late 18th century wedding dress of Isabella MacTavish Fraser.

Cloth and clothing provide unique windows into the past that few other objects from history can compare with. More than just a piece of fabric, clothing provides outlets for the expression of personal and cultural identity, place and time – they are the legacy bearers of our vast personal and social histories.

The wedding dress of Isabella MacTavish is a remarkable example of this. As the only known, and complete, women’s tartan gown of its era to survive (Inverness Museum and Art Gallery 2020), the dress is essential to our understanding of the art of dressmaking and the lives of women in the Highlands in the late 18th century. Most importantly, the gown shines a light onto its wearer, Isabella MacTavish, and her story.

Isabella MacTavish Fraser

Early Life

Born to John and Anne MacTavish on the 3rd of January 1760, Isabella MacTavish Fraser lived and was raised on a farm in the small township of Ruthven, in the parish of Dores, Stratherrick (Watson 2020).

Ruthven, situated on the tranquil banks of Loch Ruthven, was on the former lands of the Frasers of Lovat before they were seized by the Crown following the end of the Jacobite Risings in 1745. Ownership of Ruthven, however, was returned to the Frasers of Lovat on the passing of the Crown Lands - Forfeited Estates Act (1774; referred to in Fraser vs. Lord Lovat (1898)).

Image provided by Am Baile/Jack Watson Photography

Image provided by Am Baile/Jack Watson Photography

Looking onto Loch Ruthven, South East of Loch Ness. Today, the loch is a RSPB Nature Reserve and an important breeding site for Slavonian Grebe waterbirds.

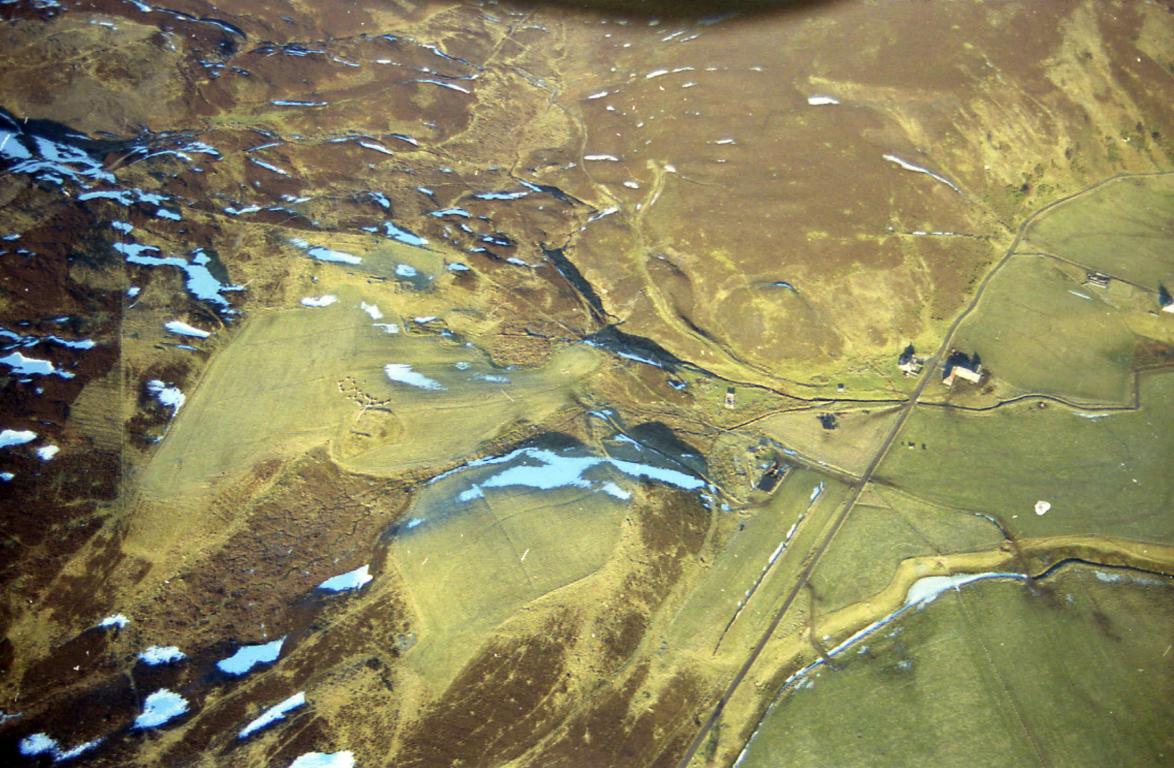

Image provided by Am Baile/The Highland Council Archaeology Unit

Image provided by Am Baile/The Highland Council Archaeology Unit

An aerial view of Ruthven and neighbouring Moy and Dalrossie from the South West. Ruined enclosure buildings and Clearance heaps are visible in the image.

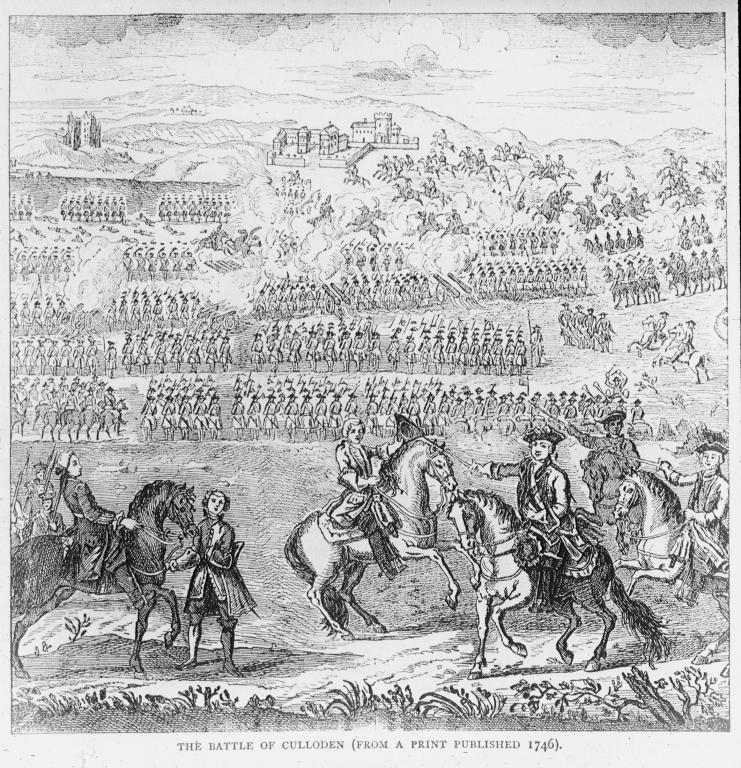

While there is little information pertaining to her early life, Isabella MacTavish Fraser grew up in a truly dark period of history in the Highlands and Islands. The devastating aftermath of the ‘45 Jacobite Risings rippled intensely throughout the Highlands, with anti-Highland sentiment still rife within the British government, army, and upper class. Almost immediately after the infamous Battle of Culloden, the violent pacification of Highlanders ensued.

Crown acts, including the Act of Proscription (1746) and the Heritable Jurisdictions Act (1746) saw the systematic targeting of the clan system and the forfeiture of ancestral lands. A new section of the Act of Proscription, known as the notorious Dress Act (1746), criminalised the wearing of traditional male Highland dress for almost 40 years (Martin 2016). This act was repealed in 1782.

In addition to the ruthless acts enforced by the Crown, the community at Ruthven was left with the immovable and permanent physical reminder of the fighting which affected to many local families in the area in the looming ruins of Ruthven Barracks.

A former British military base, Ruthven Barracks were constructed in the early 18th century to enforce the Disarming Act of 1716, following the Jacobite Risings of 1715.

Ruthven Barracks

Ruthven BarracksImage provided by VisitScotland/Airborne Lens

Aerial view of Ruthven Barracks from the North West.

Image provided by Am Baile/Highland Libraries

Image provided by Am Baile/Highland Libraries

Illustration of Ruthven Barracks, also known as Ruthven Castle, taken from Charles Cordiner's 1788 volume 'Remarkable Ruins and Romantic Prospects'.

The Dress

“There are many stories woven into the very fabric...a tacksman’s servant and her life in rural Inverness-shire...the stories of her descendants and their experiences of wearing their ancestor’s dress and the story of how the dress was made and what that tells us about textile production in the late 18th century Highlands.”

- extract from the story 'Isabella MacTavish', anonymous

In January 1785, Isabella MacTavish Fraser, now in her mid-twenties, married Malcolm Fraser of Stratherrick. One object that remains as a reminder of this special occasion is, of course, Isabella’s wedding gown which has been worn by several brides in the family down the generations.

Down to each stitch, the gown tells a fascinating biography of Highland dressmaking in the late 18th century. The dress was entirely hand stitched, based on a form of a robe à l’anglaise style popular in the 1740s, characterised by its funnel-shaped bust and deep pleats on the back of the skirt (Northwest Territory Alliance 1997).

Isabella MacTavish wedding dress reconstruction

Isabella MacTavish wedding dress reconstructionImage provided by Ewen Weatherspoon © Inverness Museum and Art Gallery

The wedding dress of Isabella MacTavish Fraser.

The gown was not made by a professional seamstress. Rather, it has been suggested that the gown was sewn by members of the bride’s family or, potentially, Isabella herself (or both!; MacDonald 2018; Watson (undated)). This revelation gives an entirely new dimension and level of emotion to the wedding dress. While we will never know the true identity of the seamstress(es) at work here, the hours of passion and care put into hand-stitching this dress, possibly work by several family members, is incredibly moving.

The fabric chosen to construct the dress is also woven with fascinating stories. Examination of the structure of the tartan setting in the fabric sheds light onto local or weaver style preferences, in this case opting for an asymmetric spacing – echoing a popular choice observed amongst other 18th century examples (MacDonald 2018).

Colour and the quality of dyes was also of great significance in Highland dress (Cheape 2008). The choice of dyes is particularly noteworthy, particularly the use of cochineal, an expensive addition which is commonly associated with individuals of higher status in this period. Dye analysis has also provided us with an earliest possible date for the fabric – 1775. This is associated with one of the dyes used to produce the green stripes in the fabric, thought to be Quercitron, introduced to UK in 1775 (MacDonald 2018).

In 2019, work by researchers on the Isabella Project, led by Rebecca Olds of Timesmith Dressmaking, aimed to construct a replica wedding gown. The replica gown, which took two days to complete, uncovered further secrets surrounding the dressmaking process (Olds 2019).

You can watch a short documentary on the Isabella Project by historical dressmakers American Duchess below.

Legacy

“The dress, for me, is a celebration of Highland women and Highland culture. It is a physical representation of something very much left out of the Highlands narrative; women and their dress...it is a physical representation of the concept of dùthchas; that strong link between the people and the land...”

- Extract from the story 'Isabella MacTavish', anonymous

The wedding gown of Isabella MacTavish is an undeniable icon of 18th century Highland ladies wear. At a time not far removed from the criminalisation of Highland dress, this gown is a celebratory symbol of Highland culture in the face of adversity and years of repression. Each thread - carrying the weight of countless stories. Each weft - a testament to the art of Highland dressmaking. Every detail - holding precious memories and the timeless joy of generations of families coming together in marriage.

It is no wonder that the gown and its story continues to captivate and inspire thousands of visitors each year at Inverness Museum and Art Gallery!

Further Reading

Interested and would like to read more about 18th century Highland dress? Explore more at:

Highland Threads online exhibition: https://highlandthreads.co.uk/exhibition

Joanne Watson, the Sassenach Stitcher: https://www.joannafwatson.co.uk/

References

Cheape, H. 2008. Tartans, dye analysis and Highland dress. [Online]. The Scottish Government. [Accessed 17 August 2022]. Available from: https://archive.parliament.scot/s3/committees/eet/inquiries/tartan/TB6_HughCheape.pdf

Fraser vs Lord Lovat [1898]. SLR 35.

Act of Proscription 1746. (c. 39). [Online]. London: HMSO.

Heritable Jurisdictions Act (Scotland) 1746. (c. 43). [Online]. London: HMSO. [Accessed 17 August 2022]. Available from: https://www.legislation.gov.uk/apgb/Geo2/20/43/introduction

Inverness Museum and Art Gallery. 2020. The Isabella Project [online]. Available from: https://www.highlifehighland.com/inverness-museum-and-art-gallery/the-isabella-project/

MacDonald, P. 2018. Tartan from Isabella Fraser’s Wedding Dress 1785. [Online]. [Accessed 17 August 2022]. Available from: http://www.scottishtartans.co.uk/Isabella_Fraser_-_Wedding_Dress_c1785.pdf

Martin, N. 2016. After Culloden. [Online]. University of Stirling Centre for Scottish Studies. [Accessed 17 August 2022]. Available here: https://stirlingcentrescottishstudies.wordpress.com/2016/04/29/after-culloden/#_ftn1

Northwest Territory Alliance. 1997. Highland Wedding Dress - # 541. United States: Northwest Territory Alliance.

Olds, R. The Isabella Project. [Online]. Timesmith Dress History. [Accessed 17 August 2022]. Available from: https://www.timesmith.co.uk/isabella-project

Watson, J. Undated. The dress. [Online]. The Sassenach Stitcher. [Accessed 17 August 2022]. Available from: https://sassenachstitcher.com/the-dress/.

Watson, J. 2020. Isabella and Malcolm, and their children [online]. The Sassenach Stitcher. Available from: https://sassenachstitcher.com/isabella-and-malcolm/