St. Kilda - Life on the Edge

A little over 40 miles west of North Uist lay the isles of St. Kilda - an archipelago of islands on the western fringes of Scotland. The islands, which tower over the rough seas of the Atlantic, have long been a source of fascination and inspiration for people all over the world and are renowned for their rich natural and cultural heritage. Join us this week as we explore the fascinating histories and the events that led to the evacuation of the last St. Kildans, now 92 years ago.

Early History

The islands of St. Kilda were formed around 60 million years ago, the remnants of an eroded Palaeogenic volcano (Gillen 2013). The archaeological evidence for the continuous habitation of the largest island of the archipelago, Hirta, spans more than two millennia. Neolithic pottery sherds and a stone quarry at Mullach Sgar, worked over 5,000 years ago, mark the earliest evidence of the island, the largest of the St. Kilda islands. Excavations at an area to the east of the main settlement, Am Baile or the Village, revealed that this activity very much continued through the Bronze and Iron Ages (Blair 2021).

The earliest written record which can be linked to St. Kilda can be traced back to 1202 AD, to the writings of an Icelandic cleric who refers to the islands under the Norse 'Hirtir' (Fleming 2005). The Viking influence on the islands are also apparent in place names which remain - Oiseval, Ruaival, and the isles of Soay and Borerary. An abandoned medieval village at Tobar Childa on Hirta, devastated by severe storms which have battered the isles for centuries, was rebuilt in the 19th century. The ruins of cleiteans, bothy structures unique to the islands, are also found throughout the St. Kilda archipelago.

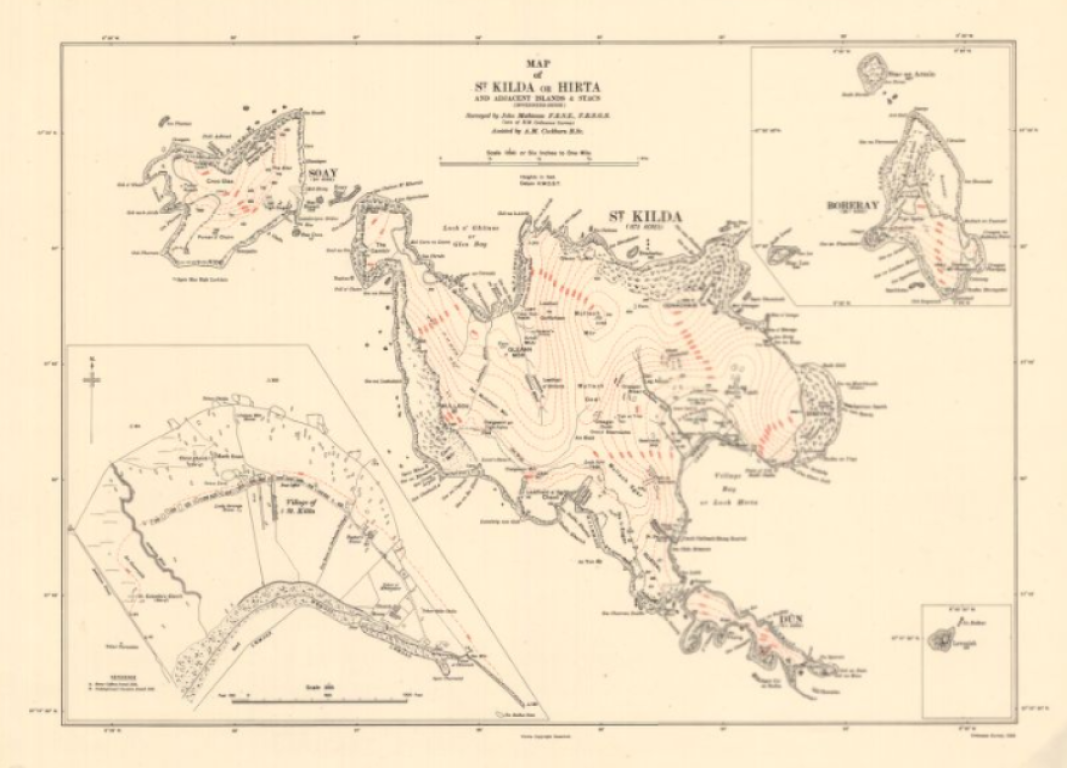

Image provided by National Library of Scotland/Ordnance Survey

Image provided by National Library of Scotland/Ordnance Survey

1928 map of Hirta and its adjacent isles (Ordnance Survey 1928)

It is thought that the population of St. Kilda never exceeded 2,000 people in its history. Yet, throughout the centuries, this community was entirely self-sufficient (Drysdale 2020). However, with an increasing number of visitors frequenting St. Kilda as centuries went by, word of the abundance of the natural environment on the islands also spread. Visiting vessels arriving in the Village Bay also carried with them the constant threat of new diseases.

St. Kildans suffered a significant outbreak of leprosy in 1684 and, in 1724, a disease thought to have been none other than smallpox devastated the islands population. After another suspected smallpox epidemic in 1727 (Stride 2009), the loss of islanders was deemed so significant that families from the Isle of Harris were brought over to revive the population (Gillies 2017).

Life on St. Kilda

Community life on St. Kilda in the 19th and 20th centuries can be largely pinned down to one word: endurance.

Diet

No trees or shrubs grew on the islands making the community and any sewn food crop vulnerable to the extreme and often volatile weather conditions. The islanders maintained a staple diet of meat from the island's seabirds and, when possible, meat and dairy products from the small sheep and cow populations on the island (MacLean 1977; Johnson 1775). Islanders also survived off of sparse potato and barley crops grown in the well drained soils of the Village Bay. The vicious storms which ravaged the islands from September to March of any given year made fishing generally impossible. In its stead, islanders opted for consuming eggs from plentiful seabird populations found frequenting the rocky crags, stacks, and cliffs of the islands (Rosie 2016; Gillies 2017). The eggs were stored in peat ash for preservation in the winter months (National Records of Scotland [no date])

Education

Until 1884, education and schooling on St. Kilda was dependant on the level of interest held by resident missionaries to the island. A visit to St. Kilda's first school by the Reverend MacAulay in 1758 , established by the Scottish Society for the Propagation of Christian Knowledge, found only four of the islanders to be literate. In the early 1900s, the island's school came under the wing of the Gaelic School Society. Following this move 44 students were noted in the school register, a quarter of which were between the ages of 20 and 40 (Am Baile [no date]).

The year 1884 marked the appointment of St. Kilda's first dedicated schoolmaster, a Mr Campbell, who taught his students in a room in the factor's house. While Campbell did not remain in his post for long regular lessons persisted until the evacuation of the island in 1930, with a new school house built to accommodate lessons in 1898 (Am Baile [no date]; National Records of Scotland [no date]).

Communication

Separated by sheer distance and severe weather, St. Kildans had limited contact with outside communities. In the late 19th century, there were only two ways islanders in need could communicate with communities in the Outer Hebrides. Firstly, by bonfire which could, of course, only work on a night with clear skies. The second was by means of the St Kilda “mailboat”(National Records of Scotland [no date]; National Trust for Scotland 2020). This was a St Kildan tradition whereby islanders placed their mail into small waterproof ‘boats’ and threw them into the sea, hoping that they would be picked up by passing trawler vessels.

Within the island, however, regular communication was established in the form of a St. Kildan "Parliament". This was an informal meeting held every weekday morning between the men of St. Kilda, where together they would detail daily work tasks and divide up resources according to the needs of each family. A separate meeting was held between the women of the community (Am Baile [no date]).

While increasing tourism to the islands in the 19th and 20th centuries allowed St. Kildans to obtain goods like tea, sugar, flour and tobacco and sell their wares, including St. Kilda's tweed, the islanders were constantly under the threat of new incoming diseases including tetanus and boat-cough (National Records of Scotland [no date]). Illness outbreaks were becoming a regular feature of St. Kildan life and a significant factor in the declining population of Hirta.

Health

Medical care and provisions were extremely limited on the island. Nurses had been provided to St Kilda up until 1890 by the landowner, at which point the final nurse Miss MacLeod requested to be reassigned citing that she had “given up hope of satisfying the islanders due to their peculiar customs and prejudices" (National Records of Scotland [no date]).

In February 1914, following the recommendations of the 1904 Report of the Medical Relief Committee and the 1912 Dewar Report into healthcare provision, a salaried nurse – Nurse MacLennan – was the first appointed to care for the St. Kildans under the new Highlands and Islands Medical Service. In September 1914, her successor Nurse Aitchison wrote:

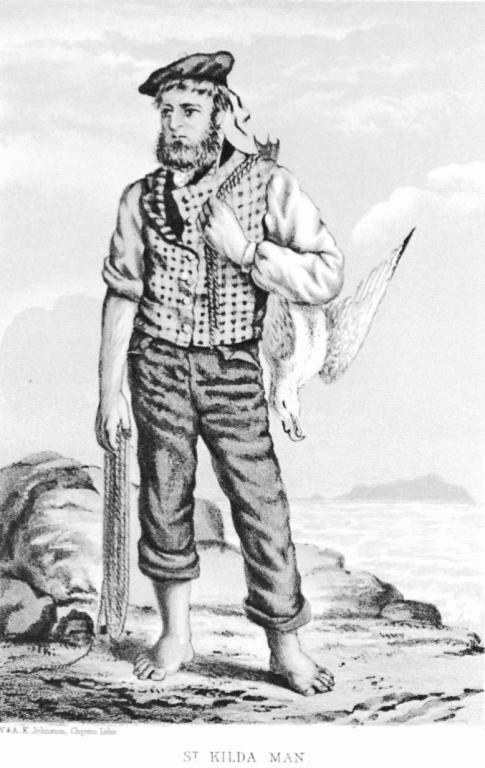

Image provided by Am Baile/Highland Libraries

Image provided by Am Baile/Highland Libraries

Sketch of a St. Kilda man taken from George Seton's 1878 volume 'St. Kilda Past and Present'.

Image provided by Am Baile/Edinburgh and Scottish Collection: Edinburgh Central Library

Image provided by Am Baile/Edinburgh and Scottish Collection: Edinburgh Central Library

Woman with a scythe taken in the 1920s, St. Kilda.

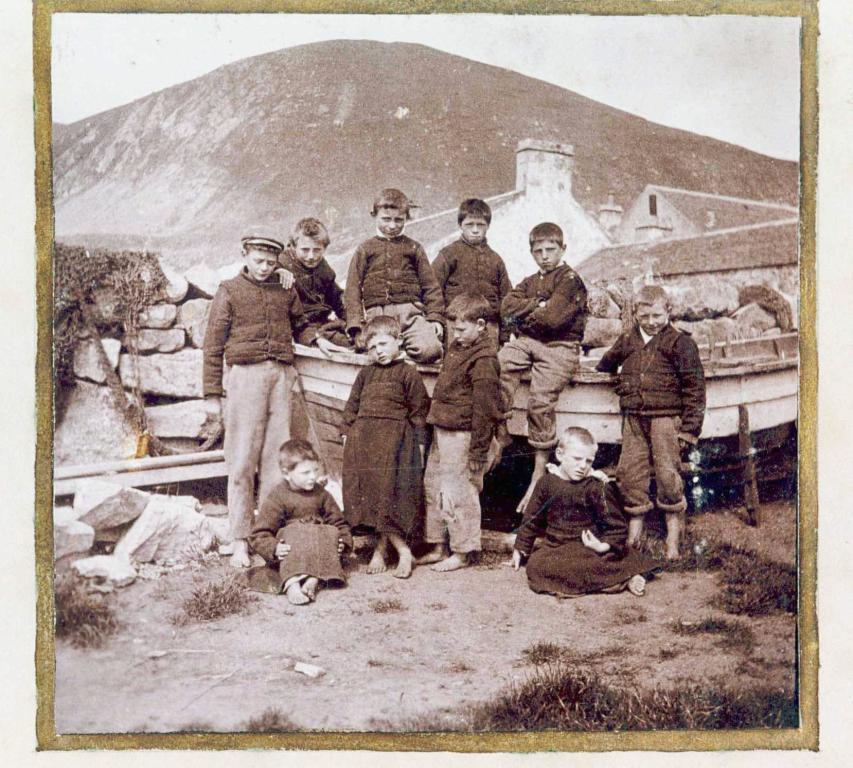

Image provided by Am Baile/Highland Archive Centre

Image provided by Am Baile/Highland Archive Centre

St. Kilda School Boys, c. 1905. From the Highlands and Islands Medical Services Committee and Report Collections.

A winter here is quite long enough for any trained nurse. There is so much wet weather and no roads, that life here is imprisonment to any who has led an active life... I have only had fresh meat once this year. I have had no butter for weeks nor any fat of any kind. I had no potatoes and had to live on scones, now I cannot even have scones regularly, I have no milk.

- Note from Nurse Aitchison dated 26 September 1914. Medical Services Files (Highlands and Islands), HH65/12).” (National Records of Scotland [no date]).

Following Aitchison, eight more nurses took up post at St Kilda prior to its evacuation (National Records of Scotland [no date]).

Evacuation

While the rocks and crags are certainly romantic, there was nothing romantic about the decision to leave the islands. By 1930, life on the islands was no longer sustainable for the last 36 inhabitants. On the 10th May 1930, 20 of the remaining native St. Kildans wrote a letter to William Adamson, the Secretary of State for Scotland at Westminster. It read:

Sir,

We the undersigned the natives of St Kilda, hereby respectfully pray and petition H.M. Government to assist us all to leave the island this year and to find homes and occupation for us on the mainland.

For some years the man power has been decreasing, now the total population of the island is reduced to thirty six. Several men out of this number have definitely made up our minds to go away this year to such employment on the mainland. This will really cause a crisis as the present number are hardly sufficient to carry on the necessary work of the place.

These men are the mainstay of the island at present, as they tend the sheep, do the weaving and look after the general welfare of the widows. Should they leave the conditions of the rest of the community would be such that it would be impossible for us to remain on the island another winter.

The reason why assistance is necessary is, that for many years Saint Kilda has not been self supporting, and with facilities to better our position, we are therefore without the means to pay for the costs of removing ourselves and furniture elsewhere. We do not ask to be settled together as a separate community, but in the meantime we would collectively be very grateful of assistance, and transference elsewhere, where there would be a better opportunity of securing our livelihood.

We are Sir

Yours Respectfully,

Lachlan McDonald no16

Finlay Mackinnon no1

Donald E McKinnon no1

Norman McKinnon Sen no1

Norman McKinnon Jun no1

Finlay His mark Gillies no7

Finlay His mark MacQueen no2

Donald Gillies no13

Ewen McDonald no16

John R MacDonald no9

Neil Ferguson Jun no8

Neil Ferguson no5

Wid Christina McQueen no11

Wid Annie J. Gillies sen no18

Wid Annie D. Gillies no14

Mrs Rachel Ann Gillies no14

Mrs Rachel MacDonald 16

Mrs Wid N Gillies no7

Mrs Wid Ewen Gillies no12

Mary Ann Gillies no12We the undersigned testify that the foregoing statement is correct.

Signed

Doug. Munro (Missionary)

Williamina M. Barclay (Queen’s Nurse)

-Petition to Secretary of State for Scotland signed by the islanders of St Kilda requesting government assistance to leave the island, 10 May 1930 (National Records of Scotland [no date])

The decision to leave was not taken lightly. For some people St Kilda was the only life they had ever known. The final nurse for St. Kilda, Williamina Barclay, wrote in July 1930:

Every day makes me more sure that it [leaving the island] is a step in the right direction... One problem solved itself this morning, the girl whom you saw in no. 14 died. This is only another instance of the difficulties of St Kilda, her end was so distressing and I had to fight the battle single handed. I am looking forward to seeing the people happily settled on the mainland." (Agriculture and Fisheries Department file, AF57/27).

-Note from Nurse Barclay dated 21 July 1930. (Agriculture and Fisheries Department file, AF57/27; National Records of Scotland [no date]).

On the 29th August 1930, the final 36 St Kildans boarded the ship HMS Harebell and departed Hirta, many for the final time, in hopes for better prospects and a greater quality of life in Morvern, Oban, Inverness, Portree and Stromeferry. MacLean (1977) wrote:

The morning of the evacuation promised a perfect day. The sun rose out of a calm and sparkling sea and warmed the impassive cliffs of Oiseval. The sky was hopelessly blue and the sight of Hirta, green and pleasant as the island of so many careless dreams, made parting all the more difficult. Observing tradition the islanders left an open Bible and a small pile of oats in each house, locked all the doors and at 7 am boarded the Harebell. Although exhausted by the strain and hard work of the last few days, they were reported to have stayed cheerful throughout the operation. But as the long antler of Dun fell back onto the horizon and the familiar outline of the island grew faint, the severing of an ancient tie became a reality and the St Kildans gave way to tears.

Contemporary St. Kilda

The St. Kilda of today is a renowned area of natural beauty and cultural significance and, as the only dual UNESCO World Heritage Site in the UK, it's importance is recognised worldwide. Now owned and maintained by the National Trust for Scotland, the isles have been a permanent base for the Ministry of Defence since 1955. While St. Kilda has no permanent residents, Hirta today is very much a working island - host to National Trust for Scotland rangers and conservators all working to protect the natural and cultural heritage of the islands against the elements, Ministry of Defence employees and scientists working on the St. Kilda Soay Sheep Project.

While the last of the native St. Kildans passed away in 2016, the extraordinary history and legacy of St. Kilda is being kept alive by the work of the National Trust for Scotland. Thanks to their work, the islands remain an incredible window into the past, still a buzz with tales of old.

Further Reading

From the Edge of the World - A blog by the National Trust for Scotland rangers working on St. Kilda. Discover more about their work here

Stories from St. Kilda - for a deeper dive into the fascinating history of St. Kilda. Learn more here

References

Am Baile. No date. St. Kilda Schoolboys c.1905. [Online]. [Accessed 01 September 2022]. Available from: https://www.ambaile.org.uk/search/?searchQuery=st+kilda

Am Baile. No date. The St. Kilda Parliament. [Online]. [Accessed 01 September 2022]. Available from: https://www.ambaile.org.uk/search/?searchQuery=st+kilda

Blair, A. H. 2021. ARO42: Hirta, St. Kilda: Archaeological Investigations. [Online]. Glasgow: Archaeological Reports Online. [Accessed 01 September 2022]. Available from: https://www.archaeologyreportsonline.com/PDF/ARO42_St_Kilda.pdf

Drysdale, N. 2020. Silence surrounds the mystical St Kilda 90 years after mass evacuation of residents. The Press and Journal. [Online]. 18 August 2020. [Accessed 01 September 2022]. Available from: https://www.pressandjournal.co.uk/fp/past-times/2356496/silence-surrounds-mystical-st-kilda-90-years-after-mass-evacuation-of-residents/

Fleming, A. 2005. St Kilda and the Wider World: Tales of an Iconic Island. Oxford: Windgather Press.

Gillen, C. 2013. The Geology and Landscapes of Scotland. Edinburgh: Dunedin Academic Press.

Gillies, D. J. 2017. The Truth about St. Kilda: An Islander's Memoir. Edinburgh: Birlinn.

Johnson, S. 1775. A Journey to the Western Isles of Scotland. [Online]. [Accessed 01 September 2022]. Available from: https://www.gutenberg.org/files/2064/2064-h/2064-h.htm

MacLean, C. 1977. Island on the Edge of the World - The Story of St. Kilda. Edinburgh: Canongate Books.

National Records of Scotland. [No date]. Stories from St. Kilda. [Online]. [Accessed 01 September 2022]. Available from: https://www.nrscotland.gov.uk/research/learning/features/stories-from-st-kilda

National Records of Scotland. [No date]. Transcription: Petition to Secretary of State for Scotland signed by the islanders of St Kilda requesting government assistance to leave the island, 10 May 1930. [Online]. [Accessed 01 September 2022]. Available from: https://www.nrscotland.gov.uk/files//research/StKildaFeature-AF57-26-3Transcription.pdf

National Trust for Scotland. 2020. St. Kilda mailboat's epic journey. [Online]. [Accessed 01 September 2022]. Available from: https://www.nts.org.uk/stories/st-kilda-mailboats-epic-journey

Ordnance Survey. 1928. Map of St Kilda or Hirta and the adjacent islands. 1:10560. [Online]. [Accessed 01 September 2022]. Available from: https://maps.nls.uk/view/74400299

Rosie, A. 2016. St. Kilda islander's diet secrets revealed. BBC News. [Online]. 29 December 2016. - [Accessed 01 September 2022]. Available from: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/av/uk-scotland-38457553

Stride, P. 2009. The 1727 St. Kilda Epidemic: Smallpox or Chickenpox? Journal of the Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh. [Online]. 39. [Accessed 01 September 2022]. Available from: https://www.rcpe.ac.uk/college/journal/1727-st-kilda-epidemic-smallpox-or-chickenpox