Flora MacDonald's Tartan

It goes without saying that Flora Macdonald is probably one of the most well-known Highland women. Her image (normally the 1749 portrait by Allan Ramsay) has been used for well over 100 years to market the Highlands and items ranging from sewing needles, shortbread, and tartan. However there has not been a great amount of research into items owned by her, including her dress.

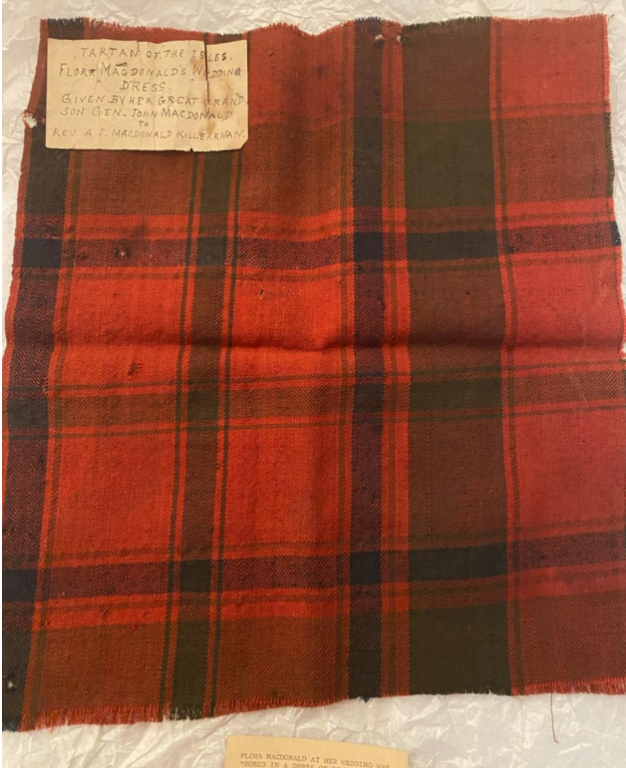

On 27th May, I found a piece of tartan in a box at the West Highland Museum which is labelled as being from Flora Macdonald’s wedding dress. I have used this sample to re-create what she may have worn.

THE FINISHED RECONSTRUCTION

Join Joanne Watson as she takes us through the process of developing and reproducing the tartan used in 18th century Highland heroine Flora's McDonald's wedding dress.

Getting Started

In May 2021, when looking through a box of tartan in storage at the West Highland Museum (WHM), I found a piece of tartan which had been mislabelled on the museum’s AdLib system. It had a label attached to it which stated that it had been worn by Flora MacDonald at her wedding on 6th November 1750.

Tartan fragment belonging to Flora MacDonald's wedding dress held in the collections of the West Highland Museum.

Tartan fragment belonging to Flora MacDonald's wedding dress held in the collections of the West Highland Museum.Image provided by Joanne Watson

I knew immediately that I wanted to recreate the tartan, but was unsure how to go about it initially. A friend put me in touch with a small mill in the Borders who initially said they could reproduce the tartan, and even visited the museum to look at the tartan, which was the basis of my application to the Spirit: 360 project. I was delighted when I found out that the funding would be awarded to pay for the tartan to be reproduced. However, following the award, unforeseen circumstances meant I had to explore new producers for the tartan.

I then decided to look for a hand weaver with the required skill to reproduce the tartan, and spoke to several before deciding upon Ashleigh Slater (Tartan Caledonia) in Blairgowrie. I had done a ‘learn to weave’ class with Ashleigh a few years ago and knew him to be a very nice person who I could depend upon. He was also UHI’s Graduate Student of the Year 2020, which he was awarded for his excellent work with a group of fellow creatives during lockdown (which he did on top of his academic work).

Ashleigh visited the museum at the beginning of 2022 to look at the tartan, took lots of photos and measurements, and then spent over 100 hours doing research into 18th century weaving techniques (which are vastly different to today). Ashleigh then wove a sample with the sort of weaving yarn he regularly uses, but it was far too soft and had too much drape for it to be used.

Ashleigh Slater and his assistant Lorraine examining tartan in the WHM collection.

Ashleigh Slater and his assistant Lorraine examining tartan in the WHM collection.Image provided by Joanne Watson

I was also given permission by Vanessa Martin, the curator & manager of WHM, to take a sample of each thread for dye analysis. This was done by Edith Sandström, a PhD candidate at the University of Edinburgh. To summarise; there were rare dyes used for the orangey brown (possibly some kind of lichen, but not one that has been found in any other tartan analysed at the National Museum of Scotland (NMS) laboratories) and the blue was dyed with Saxon blue which helps date the tartan to mid-late 18th century.

The next phase of the project involved trying to find a suitable yarn to reproduce the tartan. The original was made from the now extinct Dunface sheep, which were once commonplace in the Gàidhealtachd (mainly replaced by the Cheviot and the Blackface). The Dunface was an ancient breed, similar to a Shetland or the Soay today in size with a similar fleece. There isn’t a breed today with a dyeable fleece, but a mixture of Shetland and Cheviot might be quite similar.

IN SEARCH OF FLORA'S DRESS

There are two references to what Flora wore for her wedding in books published in the early 20th century. One claims that she wore a ‘robe of Stuart tartan’ which had been given to her by a ‘lady friend’ on the promise that she wear it for her wedding.

However, in 1938 a footnote in MacDonald’s The Truth About Flora MacDonald stated that:

Flora MacDonald’s black silk marriage dress was in the possession of Miss Emily Livingston, Edinburgh (a great-great-granddaughter), until her death a few years ago. After her death it was taken by a relative to Vancouver, Canada.

It was this quote which inspired me to see if I could find any living relatives of the relative in Vancouver, Canada, through Ancestry.com (something I did for the Highland Threads project I worked on during lockdown) and whether they would be happy to talk to me about the dress, and perhaps share a photograph.

The route the dress, or rather what is left of it, took to its current owner is not one I was expecting. It has been passed down through the family of Flora’s fifth child, James. Most material culture associated with Flora today has passed through the hands of her grand-daughter, Flora Frances Wylde, daughter of Flora’s sixth child, John, and author of an 1870 ‘biography’ of her famous granny.

Here is photographic evidence of what remains of Flora’s wedding dress. As you can see, it was cut up in the early 1920s (the style of the subsequent dress is about 1923/4) and does not survive in its original state sadly.

The repurposed dress. The circled area represents all that survives of the original dress.

The repurposed dress. The circled area represents all that survives of the original dress.Image provided by Current Owner

The current custodian does not have any written evidence in her possession to back up the claim Flora wore this for her wedding, however given the very large sett of the tartan which meant it could have only been woven for an arisaid/plaid and not dress material, I decided that I would indeed make a black silk dress to accompany the ‘wedding’ tartan arisaid.

A STITCH IN TIME: RECREATING 18TH CENTURY FASHION

STAYS, SHIFTS AND UNDERFASHION

STAYS

In order for an 18th century dress to look correct and give the correct silhouette, accurate undergarments are first required. Although a pair of Flora’s stays (corset) are on display at Dunvegan Castle in a glass case surrounded by other Jacobite memorabilia, these stays date from a later period (1780-1790) and a replica would not provide a correct silhouette for a 1750 dress.

Flora MacDonald's Stays (1770-1780) on display at Dunvegan Castle, Isle of Skye

Flora MacDonald's Stays (1770-1780) on display at Dunvegan Castle, Isle of SkyeImage provided by Joanne Watson

So, I chose to use a pattern in Baumgarten and Watson’s excellent 'Costume Close Up' which offers a scale diagram of a set of stays made in England in 1740-1760 which is in the collection of Colonial Williamsburg in the US.

I made the stays entirely out of linen and boned them with reed, materials which are both entirely biodegradable (which might be one of the reasons hardly any originals exist today) and the nearest available today in terms of historical accuracy. They took me six weeks, on and off, to make as it is quite a dull process quilting the panels and the sewing of the panels together is extremely tough on the hands (I required pliers to pull the needle through the layers of fabric). I was very happy with the resulting stays and intend to use these in the future for educational purposes.

Collage of the stages of stays construction.

Collage of the stages of stays construction.Image provided by Joanne Watson

SHIFTS

After making the stays, I made a linen shift (like a modern nightdress, but in the 18th century was worn by women of all levels of society as the first layer of underwear and also used to sleep in and almost always made of linen as it could soak up the sweat and would wash well).

Shifts are very simple to make, although they require a very small stitch count per inch so that the seams are sturdy. All seams are sewn twice for added robustness in washing, and were meant to last. This only took a couple of days to sew (I have made them before) as it is a very easy pattern – a shift is essentially squares and rectangles sewn together in a particular manner) and I have to decide to wear it myself now as a nightdress. It is the most comfortable nightwear I own, and intend on purchasing more handkerchief linen to make myself more.

Linen shift overlayed by stays. Model: Annette McKittrick.

Linen shift overlayed by stays. Model: Annette McKittrick.Image provided by Joanne Watson

PETTICOATS

The final item of underwear required was a hoop petticoat. For this I used a pattern in Patterns of Fashion 5 of a hoop petticoat in the collection of Newcastle Museums in England, and used hemp linen, linen thread, linen tape and cane (for the boning).

Hemp linen is not only a fabric which has been used for centuries, but has a beautiful drape and doesn’t require any pesticides, and is apparently anti microbial as well. This petticoat has to be one of the strangest things I have sewn, and attaching the long lengths boning was also challenging, but it gives the perfect silhouette. Annette found it was comfortable to sit in and to wear, although it was a bit difficult getting in and out of the car!

The last items of underwear I made for this project is the petticoat you see in the image below. This is essentially two rectangles of medium weight linen, attached to a waistband of linen tape in a curved manner (to allow for the hooped petticoat) and took one and a half days to sew.

The hoop petticoat on underneath another linen petticoat. Notice the exaggerated hips and the much fuller skirt.

The hoop petticoat on underneath another linen petticoat. Notice the exaggerated hips and the much fuller skirt.Image provided by Joanne Watson

PIECING THE TARTAN INTO THE ARISAID

An arisaid, or earasaid in Gaelic, is the female version of the belted or Great plaid, the féileadh mór, and was commonly worn by Highland women of all levels of society from at least the 17th century, if not before. Martin Martin was the first to give a description of the arisaid in 1703, stating that:

the ancient dress wore by the women, and which is yet wore by some of vulgar, called arisad, is a white plaid, having a few small stripes of black, blue and red. It reached from the neck to the heels.

Etchings from 1745 and a painting of weddings in 1780 and 1790 give us clear visual images to how the arisaid was worn throughout the 18th century. It is my belief that the arisaid, which was once common amongst Highland dress, lives on today in the formal tartan sash sometimes worn by women in particular clan tartans, although its size and its function has changed over time; it was once essentially a very practical garment which could be used equally as a cloak or a warm bedcover, but nowadays is a small visual symbol of belonging to a particular clan.

Tartan historian Peter MacDonald wrote a paper about the MacColl tartan in 2021 in which he included Flora’s wedding tartan. While Ashleigh Slater, my weaver, and I do not agree with Peter about this tartan being a MacColl tartan (there are differences) nor about the width of the tartan based on current knowledge, he does provide some very useful information here: http://scottishtartans.co.uk/Origins-of-the-MacColl-Tartan.pdf

Ashleigh spent over 100 hours researching 18th century tartan and the lives of 18th century weavers, and he intends to study this further at the University of the Highlands and Islands this coming academic year by doing a postgraduate research degree (in preparation for a PhD), so I will not discuss his findings here.

He then spent two months weaving the tartan for this project, in between his teaching commitments.

Ashleigh spent over 100 hours researching 18th century tartan and the lives of 18th century weavers, and he intends to study this further at the University of the Highlands and Islands this coming academic year by doing a postgraduate research degree (in preparation for a PhD), so I will not discuss his findings here.

He then spent two months weaving the tartan for this project, in between his teaching commitments.

Given how much hard work had gone into recreating this tartan by both Ashleigh and myself, I did not want to cut the fabric and sew it up into an arisaid (again this made me think; this time about the value of cloth and clothing, and how much hard work was required into producing such beautiful fabric.

However, I did and thankfully did not lose much in the joining up of the pattern (that is the piece in the below photo which I donated to the West Highland Museum). I did not measure the tartan on Annette, but on myself (I am seven inches taller than her) as I intend to wear the garment in the future at reenactments events, and also plan to keep it for other educational purposes.

The original piece of tartan in the collection of the West Highland Museum (left) and a sample of Ashleigh’s reproduction on the right (also now in the collection of the West Highland Museum)

The original piece of tartan in the collection of the West Highland Museum (left) and a sample of Ashleigh’s reproduction on the right (also now in the collection of the West Highland Museum)Image provided by Vanessa Martin

The two pieces of tartan were whip stitched together with very small stitches (20 to the inch) using the green wool used in the tartan (from Ashleigh’s leftovers) and hemmed with the red wool also used in the tartan.

Several surviving arisaids have fringed edges, but others have hemmed edges (for example the ‘IC 1796’ arisaid at the West Highland Museum) and I took a creative guess that Flora would have most definitely worn hemmed arisaids over fringed ones (unfortunately the hems are not visible in her portraits).

MAKING THE DRESS

FABRIC

I chose to make the dress out of pure silk satin due to the portrait of most famous portrait of Flora (Allan Ramsay’s portrait which is in the collection of the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford), and the dress shown in figure 8. However I could not afford 30 - 40 momme silk, so I chose to purchase the thinner 19 momme satin silk and flatline it with a lightweight black linen; combining the two would give the required weight and drape needed for the dress. This is a historically accurate sewing technique, which has been in use since at least the 17th century, and on this project saved over £100.

Flora MacDonald by Allan Ramsay (1713–1784), 1749, from Ashmolean Museum, Oxford.

Flora MacDonald by Allan Ramsay (1713–1784), 1749, from Ashmolean Museum, Oxford.Image provided by Joanne Watson

Most silk satin in the mid 18th century measured between 19” – 24”, with 20” being the most common, so I decided to cut panels 20” wide, whip stitch these together with many tiny stitches (this took me two or three weeks, I lost count) and then sew these panels together. I made them too long on purpose as I knew I would have to fit these to Annette and I was making this dress in an eighteenth century manner (drafting it on her body rather than following a pattern as we do today). I much prefer the eighteenth century way of making clothing, as it is made to fit the person and therefore you get a perfect fit.

FINISHING TOUCHES

The final part of the drafting on the body process was to draft the bodice. This is done by draping the lining on the body and pinning it to the stays, drawing around it (I used a chalk pencil due to the black fabric, but pencil could easily be used on lighter fabric), cutting and then taking off the body. This forms a pattern for the outer fabric, and then each panel is whip stitched together before being sewn together.

Drafting the skirt. Model: Annette McKittrick.

Drafting the skirt. Model: Annette McKittrick.Image provided by Joanne Watson

I then spent 22.5 hours sewing and only had 2.5 hours sleep so that the outfit would be ready the following afternoon to take photos of Annette in Culloden. This long sewing session was an absolute revelation for me; it made me reflect about the working conditions and wages that seamstresses and mantua makers had, many of whom also worked under very tight deadlines (but did not have the benefit of electric light, air conditioning and copious amounts of tea).

I have spent over a year on this project, and it took much, much longer than anticipated. There were several large hurdles to overcome, which I did (sometimes with help from friends) and I have learned so much from the process. I would like to express my sincerest thanks to the Spirit of the Highlands for funding the production of the tartan, to Vanessa Martin at the West Highland Museum for her encouragement and support, to Annette McKittrick for agreeing to go out of her comfort zone and model.